IBM Fundamental And Algorithmic Analysis: Will Big Blue Bring Big-Time Blues?

Confira nosso último artigo (13/11/2014 )no Seeking Alpha: IBM Fundamental And Algorithmic Analysis: Will Big Blue Bring Big-Time Blues?

Clique aqui para ler, comentar, e opinar diretamente no Seeking Alpha.

Acompanhe a performance de nossos artigos.

Summary

- IBM revenue hasn’t grown for the last 10 quarters; this Q3, the company experienced its worst earnings miss in recent history, and consequently dropped its long-anticipated 2015 growth plan.

- Currently IBM faces criticism: specifically, revenue stagnancy, poor international growth, inaccurate performance estimates, late transition to modern sectors, and stock buyback dependency have all been deemed problematic.

- Nevertheless IBM still has strengths; analysts and investors feel its past rebounds, legendary current status, strong leadership, novel-sector growth, cutting-edge research, and recent partnerships make it worthwhile despite the drop.

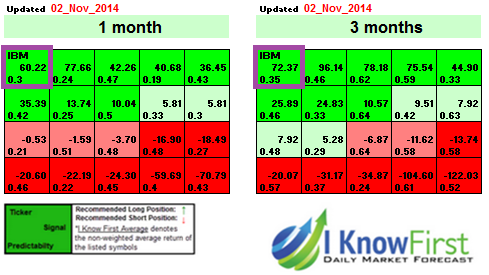

- I Know First’s algorithm predicts a bullish forecast for IBM in the 1-month and 3-month time frames.

Company Profile: International Business Machines Corporation

“I don’t think there’s any company that I can think of, big company, that’s done a better job of laying out where they’re going to go, and then having gone there.” – Warren Buffett

International Business Machines Corporation (NYSE: IBM) – more commonly known as IBM, and frequently nicknamed “Big Blue” in reference to its affinity for predominantly blue logo, packaging, and product designs – is an American multinational specializing in computer hardware and software, as well as computer and technology services. Incorporated in New York in 1911, IBM has historically established itself as, in the very least, a significantly successful player where technology is concerned: it has been called a “legendary”company, receiving routine praise for its sound balance sheet, long track record of successful growth, huge contribution to employment numbers (IBM had around 431 212 employees worldwide as of 2013, and is pivotal to employment in certain regions), and – particularly in recent decades – itsadaptability to changing technological eras. With twelve research laboratories and the record for most patents generated by a company for 20 consecutive years, IBM’s research divisions – riddled with Nobel Prize, Turing Award, National Medal of Technology, and National Medal of Science winners – have consistently shown strength; further, as a result of its capacity for innovative technological development, IBM has such inventions as the automated teller machine (ATM), floppy disk, hard disk drive, and Watson artificial intelligence system to its name. As could be expected, these and other positive attributes have meant that IBM consistently receives industry recognition: in 2012, it was ranked the second-largest U.S. firm in terms of number of employees byFortune, the fourth-largest in terms of market capitalization, the ninth most profitable, and the nineteenth largest where revenue is concerned. On a global scale, IBM was also classed as a leader: specifically, it was ranked as thethirty-first largest company in the world by Forbes in 2011. From 2011 through 2012, it consistently made headlines in other capacities, as well: it was ranked the number-one company for leaders, the number-one green company worldwide, the second best global brand, the second most respected company, the fifth most admired company, the eighteenth most innovative company… the list goes on. Analysts have also remained dedicated to IBM, with such greats as Warren Buffett investing heavily in the company Combine this kind of research productivity and public reception with a high market capitalization and annual average earnings growth of 11.10% for ten consecutive years, and it becomes relatively easy to see why IBM was, as of 2011 and 2012, viewed considerably favourably, despite the fact that it had not seen much growth since 2008.

Current Events: 10 Problematic Quarters, Q3 2014, and Reasons for the Drop

“When you’ve promised something, and you keep saying you’re going to do it, and all of a sudden you change your mind, that obviously upsets a lot of people.” – Bob O’Donnell, TECHnalysis Research

While pre-2013 IBM was, as is described above, a sight to see, the company’s recent progression has not been quite as flattering. Firstly, there is the fact that revenue has now declined for ten straight quarters (Figure 1). This phenomenon has, by many, been interpreted as a sign that the company – which, as was mentioned above, hasn’t experienced much revenue growth since 2008 – continues to stagnate, and requires revitalization.

Figure 1. IBM’s annual financials for 2009 through 2013. Notice that five-year trends for both sales revenue and gross income are decreasing. Source:Marketwactch.com

With every recent passing quarter, at least some analysts and investors have remarked that IBM – whose last few quarters have been characterized by declining sales and low productivity in services, the two sectors that have served IBM for almost two decades – is steadily losing momentum, primarily because the company, as Behrooz Najafi and Wall Street Journal’s Clint Boulton put it, is an “old” one, primarily in that it has been slow to transition from increasingly obsolete, “fading” hardware and manufacturing to cloud computing and software – the hallmarks of a more modern technological era. As of the last two years, it has been near-consensus that the company’s hardware businesses – e.g., its trademark chip manufacturing operations, which lost it $700 million in 2013 and $400 million in the first half of this year – are injuring its progress, and that its server businesses are not doing much to help. IBM has attempted responses, to be sure – while it frequently cites currency appreciation and unprecedented technological change as key factors in its recent stand-still, IBM also acknowledges its role in its own growth problems, and has therefore been making software- and cloud-related acquisitions (e.g., SoftLayer) while ridding itself of hardware commitments. Earlier this year, for example, it made a point of beginning to publicly structure a deal with GlobalFoundries – a company that could take over IBM’s profit-depleting chip business. As much as these efforts are at least minutely helpful, IBM, analysts and investors say, is still far from reaching meaningful targets.

IBM’s lack of growth alone doesn’t thoroughly account for the company’s most recent downfall, however. As much as its stagnancy is an important facet to consider in evaluating the company, IBM has been flat for about ten quarters – ten quarters during which it was still sufficiently well-regarded by investors to bypass dramatic drops in share price. This all changed this quarter, however. On October 20th, 2014, IBM publicly released its third-quarter results, and made a certain public announcement. That same morning, the company’s share prices plunged, going from $182.05 to approximately $169.15 in afternoon trading for an approximately 7% tumble, eventually dropping all the way to $166.79 in pre-market trading (Figure 2). This drastic fall, culminating in a three-year low, took with it a significant chunk of the Dow Jones Index (it was responsible for about 85 points of a 102-point fall in the Dow Jones Industrial average), concurrently managed to tank an initial $1 billion of Warren Buffett’s hard-invested finances, and, finally, even injured IBM’s rivals: Hewlett-Packard (NYSE: HPQ), EMC Corporation (NYSE: EMC), Accenture, Oracle (NYSE: ORCL), and Microsoft (NYSE: MSFT) all fell by between one and two percent.

Figure 2. IBM, going strong in the $180.00 – $185.00 share price range prior to mid-October, dove deep around October 20th. Source: Yahoo Finance

Why did IBM disintegrate quite so spectacularly now, after “just another” quarter of sub-par growth? What made Q3 2014’s results so much more disappointing than those of previous quarters?

Firstly, unexpectedly sharp slips in revenue. While some analysts say they expected currencies to be problematic and the GlobalFoundries sale to impose a massive one-time charge, very few observers were expecting that profits would come in so short of analyst estimates. Revenue fell to $22.4 billion this quarter from $23.34 billion in the previous year, while analysts expected it to rise to $23.37 billion. Net profit from continuing operations also dropped to$3.46 billion from $4.14 billion in Q3 2013. Cumulatively, IBM earned a profit of only $3.68 per share – a full 14% below the $4.32 proposed by analysts.

Secondly, these earnings misses – the worst in recent IBM history – were made even worse by the fact that they had a multitude of IBM-relevant causes. Presumably, both weaker-than-expected software sales and lower productivity in services injured third-quarter numbers. This means that both clients and the software sector were less inclined to spend on IBM; to onlookers, this may have signaled that not one, but several components of IBM business might be compromised. While IBM’s hardware segment has been categorized as problematic for some time, not all aspects of the business’s software were expected to do poorly: IBM, in fact, recently invested in software via acquisitions, and was, as of 2013, the market leader in application infrastructure and middleware software for thirteen consecutive years – a position it has now lost to HPQ. As such, seeing lower-than-anticipated software productivity may have troubled investors.

As a result of the aforementioned earnings misses, understandably, IBM’s current CEO Virginia Rometty also had to revise the company’s earnings predictions for the future, most notably by ex-ing Roadmap 2015 – a plan that promised to elevate IBM’s earnings per share to $20 by 2015 – on the very same day that the aforementioned disappointing Q3 results emerged. This was the third hit to IBM’s reputation on October 20th, and has been portrayed by analysts as perhaps the biggest reason for the mid-October drop. A forecast that had been maintained for five years and under two CEOs, Roadmap ’15 was more than just another target schema: it was a plan that, paralleling a highly successful earnings initiative in 2010, had convinced the public andWarren Buffett alike that IBM was a worthy investment. To see it so easily put to rest lowered investor trust. In analyst Bob O’Donnell’s words, “The market has punished them probably because when you’ve promised something and you keep saying you’re going to do it, and all of a sudden you change your mind, that obviously upsets a lot of people.”

It should be noted that IBM did, despite Q3’s difficulties, announce a few current positives in its Q3 results. Firstly, the company released a conclusive decision concerning the long-anticipated GlobalFoundries deal: IBM would, as predicted, hand over its chip-production business to GlobalFoundries, (restructure) paying the privately-held semiconductor manufacturing contractor $1.5 billion over the course of three years to account for the difficulties accompanying the unit; GlobalFoundries will manufacture chips for IBM’s technology for the next ten years, while IBM will continue conducting research into chip technology. Though this research will cost approximately $3 billion, and though the deal itself has resulted in a $4.7 billion pre-tax charge on IBM’s quarterly results, this move has been hailed by most analysts as a positive one, given that it will, by pushing IBM away from unprofitable hardware, eventually help to restore profits. Secondly, at least some aspects of IBM did improve: the company saw positive revenue growth in the cloud, mobile, and business analytics segments. In particular, given the company’s novel interest in the cloud business, any increase in revenue in that segment – though cloud is still expected to constitute only a small portion ($3.1 billion) of IBM’s total revenue this year ($100 billion last year) – is a good sign (hard sentence to read). Finally, some job cuts – a small but sometimes necessary part of restoring functional revenue by eliminating expenses – were detailed.

The Q3 report was not all cons, then. However, the positives cited above were not significant enough to dispel the kinds of worries that arose in the face of IBM’s sizable earnings misses, and the company’s abandonment of a committed profit-elevation plan.

As a result of these disappointments, IBM now sits at a share price of approximately $163.23. The decline has also cut about $13 billion off of IBM’s market capitalization, further immobilizing business developments.

A Few Negatives

“We are disappointed in our performance. We saw a marked slowdown in September in client buying behavior, and our results also point to the unprecedented pace of change in our industry.” – Virginia Rometty, IBM CEO

As could be expected given this month’s less-than-favourable events, IBM has been the subject of ample criticism in recent weeks. While not everyone has been quick to advocate letting the company go, with several investors rushing to point out that IBM is “far from” going out of business, several noteworthy points have been made with regards to the company’s deficiencies. In particular, its core-sector revenue stagnancy, poor international growth, inaccurate performance estimates, late transition to modern sectors, and stock buyback dependency have all been seen as problematic.

Firstly, it’s possible to say that IBM’s six-year, ten-quarter, and Q3 2014 results speak for themselves. The company’s revenue hasn’t grown for years, as has previously been pointed out by analysts like Stanley Druckenmiller – it has remained about the same since 2008, and has, in the last ten quarters, even fallen. IBM sales are also identical to what they were six years ago. Further, these aren’t just any revenue declines – the most central elements of IBM’s business – hardware, services, and software – are all declining. Once renowned for its consistency and the “stickiness” of its customer base, IBM’s hardware segment – supplying all three 1990s gaming systems (i.e., Sony, Nintendo, and Microsoft products) and Apple’s Mac computers – was stably a powerhouse at its prime: so much so, in fact, that Warren Buffett – who previously avoided the technology sector because of its volatility – chose to invest significantly in IBM. At present, however, this integral element of IBM’s business is not just declining slightly – it was so difficult to sell this year that IBM’s transaction with GlobalFoundries “could not be termed a sale”, according to some analysts: IBM had to actually pay the semiconductor contractor to take the segment off its hands. Weak sales in IBM’s software and services businesses exacerbated the problem; such wide-ranging and profound decreases in core-segment revenue and customer interest are definite negatives.

IBM isn’t solely losing out where the United States are concerned, however: allof its international divisions – located in the Americas, Europe, Middle East, Africa, and Asia Pacific – registered a decline, with the Asia Pacific region registering a high 9%. Even those international markets that were expected to grow (e.g., Brazil, India, China, and Russia) did not: they also registered a 7% drop. This makes international growth seem like a less-than-meaningful prospect for IBM.

Lower-than-average present and projected revenue, while sub-optimal, wasn’t the biggest issue this quarter. It was IBM’s failure to live up to its own past productivity and growth estimates that many analysts found problematic: the company has, on several occasions, forecasted one idea but realized another. CEO Rometty predicted that this year’s second half would help meet targets. Q3 tanked them. IBM designated Brazil as a growth market. Brazilian revenue declined. IBM announced a $1 billion restructuring plan this year to trim jobs and realign divisions for better business objectives, and what came of it? A 1%increase in expenses and 4% decline in revenues, rather than any kind of salvation. Finally, and most potently, Roadmap ’15 long promised shareholders earnings per share of $20 by 2015, and was hailed as “gospel creed” by some analysts because of its “very public nature” . And even this -the most widely-broadcasted of next steps – will now no longer be taken. These discrepancies between IBM’s predictions and realities have angered investors: it seems to some that the company might never precisely know what it’s doing next. As analyst Bob O’Donnell points out, even IBM’s delivery of bad news seemed to showcase slipshod planning: IBM threw several pieces of bad news to observers “all at once” in a move that some analysts are seeing as less-than-calculated, and mentioned its surprise at the downfall of its own recent predictions several times, with CEO Rometty calling industry changes“unprecedented”. “Some reassessment of expectations and resources” will be necessary, O’Donnell maintains, if IBM is to climb.

To be fair, re-evaluating resource distribution and reframing company focus is precisely what IBM has taken to, as of late. Rometty, in line with Microsoft (NASDAQ:MSFT) CEO Satya Nadella and his “cloud-focused world“, has made several moves to reinvent IBM, taking it from hardware to markets like mobile and cloud. The transition itself, analysts and investors agree, is necessary – as has been said previously, IBM is widely regarded as “behind”, and moving towards more cutting-edge sectors could help Big Blue get ahead. Furthermore, hardware in the U.S. is becoming difficult to navigate in the face of inexpensive global competition, as is evidenced by the fact that not just IBM is restructuring – Hewlett-Packard (NYSE:HPQ), another large player, announced its intent to differentially segment its business earlier this year, and the move to cloud has taken even such names as Oracle (NYSE:ORCL) by surprise. While the need to shift gears is a real one, therefore, the speed at which IBM’s transition has been orchestrated is not leaving onlookers impressed: IBM has been criticized as transitioning “too little, too late“, as analyst Patrick Moorhead puts it: investors and analysts alike say that Rometty’s cloud-related deals have not been sufficiently transformative (many suggest big purchases, while Rometty has consistently made smaller ones), that the effort is compromising IBM’s ability to sell off its more problematic infrastructure services, and that investors’ loyalty may well be tested by the fact that IBM’s journey is only beginning while its primary cloud competitors (e.g., Nadella’s Microsoft) are already well-established in the market. Some observers are also concerned that the transition will not run deep enough.Martha Toll-Reed, Senior Director of corporate ratings at Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services, has mentioned that “a lot of IBM’s software and services sales are still generated by hardware” – while the company may well aim to rid itself of hardware commitments, in other words, hardware may still be essential to IBM’s bottom line. If this is true, then it may be slightly problematic that IBM has sold off its entire global commercial semiconductor technology business – intellectual property and employees included – to GlobalFoundries. While keeping the business was unprofitable, disposing of rights to some uniquely “IBM” hardware and engineers may not have been the best-available option if hardware is indeed such an integral aspect of IBM’s operations. A similar argument has been made concerning IBM’s decision to diverge from services (e.g., IBM just sold its x86 server business to Lenovo Group), as well: while the global services business is seeing pricing pressure because of intense competition, Wells Fargo’s Maynard Um points out, the majority of IBM’s sales – about 55% last year – come from its services business. As such, though the transition away from hardware to software and old services to new services is viewed as a logical next step, some investors aren’t certain that it will be sufficient to propel IBM forward; in more immediate regards, given IBM’s dependence on hardware and services, $300 million workforce restructuring plan, and the appreciating U.S. currency, transitioning may be more harmful than just unhelpful.

Another frequently discussed IBM negative is the company’s buyback history and debt position. As of the third quarter of 2014, IBM has a total debt of approximately $45.7 billion. A sizable portion of this number comes from IBM’s penchant for stock buybacks: as analyst Stanley Druckenmiller points out, IBM has tripled its debt just to repurchase stock and pay dividends: specifically, since 2000, Big Blue has spent more than $108 billion on its own shares, and has paid out $30 billion in dividends – far more than it spends on advancing business via capital expenditures and acquisitions, which have cost it only $91 billion jointly. He doesn’t see this as a wise decision. Wall Street’s David A. Stockman concurs, stating that IBM “is a buyback machine on steroids that has been a huge stock-market winner by virtue of massaging, medicating and manipulating” its earnings per share, and that its financials show no hint of “value creation”. In short, if IBM needs to commit this much spending just to restore itself, and restoration has not as yet been realized, the future may be problematic.

The Positive Attributes

“You don’t get to be a 100-year-old company and $100 billion business and not continue to have to be pushed for change, for the next big thing.” – Steve Gold, IBM Watson vice-president

While it is clear that IBM may currently be more “Blue” than “Big”, it may not be entirely wise to dismiss the company solely on account of recent events and accompanying fundamentals. IBM’s past, present, and future do grant us some compelling reasons to stay involved in the company’s workings.

Big Blue’s past, firstly, can grant us some hope. Yes, IBM is down, and has been for quite some time. This, however, is nothing new. Warren Buffett first invested in this technology stock, after a near-fifty-year technology sector avoidance, precisely because of IBM’s rebound potential. The company nearly went bankrupt in the early 1990s, but rose to dominate the late ’90s and early 2000s, contributing milestones to gaming and Macs via its chip manufacturing technology – a product of its strong patents and research output. When financial crisis struck in 2007-2008, it dropped again, but former CEO Sam Palmisano succeeded in implementing Roadmap 2010, and made earnings per share double.

Secondly, it’s worth noting that the present isn’t as bad as it seems. Even with its losses, IBM is far from over and done with: according to Bloomberg, it’s still “a legendary company, a blue-chip stock, and a huge employer” with “substantial cash” (even with no growth, it generated about $2.2 billion in free cash flows) and significant access to debt markets. Some investors even argue that, adjusted for currency and divestitures, IBM’s revenues are flat, not declining, and that they cannot independently be considered a measure of growth: IBM’s margin, which the company is trying to expand, must also be taken into account. Further, many investors understandingly point out that IBM’s size almost necessitates that time be taken in implementing drastic operational structure and product portfolio overhauls.

Even if revenues are held to be declining and solely indicative, however, Big Blue’s current situation isn’t in any way too distinct from those of other large players, either – Microsoft, Oracle, and HPQ have all had to recently undergo multi-year transitions, as has been variously discussed above. HPQ and Cisco Systems (NYSE: CSCO) form even more complete parallels to IBM: both leading players in tech, they’re also flat in terms of revenue growth, but nevertheless maintain decent free cash flow. While some of these companies may well be ahead of IBM where timing is concerned, this trend signals that transitions are unavoidable in today’s climate for even the largest of technology giants; further, Microsoft’s transitional successes in particular indicate that there may be a silence after the storm for some players, if shifts are effected carefully.

True enough: part of Microsoft’s success may well have been in its timeliness. However, there is no telling that IBM couldn’t also experience a rough patch, and subsequently – if long-windedly – emerge successful: it has, after all, done so previously, with its rough 1993 move to services being hailed as the company’s salvation. Though the tactic then-CEO Louis V. Gerstner, Jr. (a top executive in his time) used to propel IBM forward in 1993 would not work now (integrated solutions have become considerably less appealing to customers, after all), IBM’s capacity for innovation is clear – on the verge of disaster, it was reborn by dint of capable leadership.

With this specifically in mind, the present should seem decently bright: IBM’s current management – if it has not as yet entirely established control of Big Blue – is at least remarkably technically strong. CEO Virginia (Ginni) Rometty has been hailed as the most powerful woman in business by Fortune this year, even in view of IBM’s two-year failures. Specifically, Fortune cites Rometty’s last few business developments – revenue growths of 69% in new IBM markets (cloud, analytics, and mobile), a deal with Apple, the Watson business group, and investments in cognitive computing – as testaments to her capability. To further specify, cloud revenues jumped 80% versus the year-ago quarter, even in disastrous Q3 2014; mobile revenues more than doubled; analytics was up 8%, and security increased 20%. Rometty also plans to implement complementary infrastructure – e.g., a network of 40 server centers in 15 countries – to aid IBM’s cloud-based software segment in taking off.

Besides signaling that IBM is presently in the hands of a strong leader, the aforementioned business developments – as well as certain partnerships – also position IBM positively as it faces its future. Specifically, IBM Watson, chip research, the company’s partnership with Apple, and its deal with Twitter are seen futuristic assets, in, I would say, decreasing order of importance.

IBM Watson, developed by IBM, is sight to see. As of 2013, IBM had spent over $16 billion on 34+ analytics acquisitions since 2005; these culminated inWatson Analytics, a suite of data-analysis services that successfully targeted small and medium businesses. Looking forward, this would already seem a favourable business to have on hand, given IBM’s newfound dedication to analytics.

As of 2011, however, Watson became much more than just a successful analytical tool: IBM, having dabbled in artificial intelligence, reinvented Watson, creating an artificially intelligent computer system that – though it may well have been slow to commercialize – was smart enough to win Jeopardy! in 2011. Since then, Watson AI has become IBM Watson (also sometimes termed “Watson Group”): a fully-fledged division of IBM dedicated to cognitive computing.

Established in January 2014 with a $1 billion budget, IBM Watson opened the doors to its four-floor HQ in late October to tremendous celebration, and for due cause. The technology is trademark IBM, augmenting work IBM has already done: a computing system that is innovative enough to learn from unstructured social media data. It is so innovative, in fact, that it’s been hailed by programmers as the trough of a new, “third wave” of computing, according to Spark Cognition CEO Amir Husain. Steve Gold, the unit’s vice president, also stands behind IBM Watson completely. “We are extremely bullish on Watson,” he said earlier this year. “The formation of the Watson Group was really the stake in the ground [to changing certain ways industries operate].” Husain concurs, noting that self-evolving learning systems like Watson are “avery key ingredient to the future of the software industry”. Given that Watson began with three partner companies and has since grown to have more than100, with another 3,300 applying for the program, he clearly isn’t the only one to think so (Travelocity founder Terry Jones, for example, also says he’s “stoked” about this aspect of IBM). The technology is also developing quickly: it’s been handed to developers in the cloud to be used in developing their own apps, is set on branching into such lucrative fields as health-care optimization and e-commerce, is available to the world beyond New York via Watson Experience Centers located in London and around the U.S., will be the focus of an incubator for start-ups, and had excellent reception when its personalization capabilities were demoed via deals with Welltok andWayBlazer. And this is just the beginning: given that Watson has accomplished so much in so short a time, Gold says, it will almost certainly branch out even further, spanning more uses and more industries (e.g., retail, hospitality, manufacturing) in the years to come. Perhaps wisely, IBM has remained comparatively humble about this technology, avoiding disclosures of how much it invests in each of its supporters – Watson needs no introduction.

While Watson may seem more than powerful enough to single-handedly boost IBM’s business, IBM has been conducting other research. Now that it has rid itself of manufacturing obligations, IBM can devote itself to integrating its old, winning technology with its new, positive attributes; that’s precisely what the company’s “brain-like chip” (called “TrueNorth”) is geared at doing. Announced in August of this year, this device has the capacity to process large quantitiesof data in real-time (something current chips cannot do), is energy-efficient, and can emulate one million human neurons. Further, IBM hopes to incorporate multi-sensory processing, and seems to believe that this chip can be used for related purposes.

While producing such innovative research output as described above, IBM has also been looking outwards; firstly, efforts to form affiliations have culminated in an enterprise partnership with Apple, announced earlier this year in the form of the “MobileFirst” deal (which, incidentally, dropped Blackberry’s share price 12% the day it was announced). The two companies will work together to deliver 100-plus industry-specific solutions and apps for iPhone and iPad, IBM cloud services optimized for iOS, AppleCare services, and package deals from IBM. This deal is advantageous to Big Blue for several reasons. Firstly, Apple is an integrated whole – while Google’s Android operating system has separate operator, device, and management levels, Apple will provide IBM with one iOS to which many users are bound. This is expected to help IBM big data and analytics penetrate the cloud market. While IBM is already renowned for providing support to organizations, this deal will help it move into customization and user engagement. Further, because approximately 98% and92% of Fortune 500 and Global 500 companies utilize Apple’s iPhone and iPad technologies – devices that IBM will now permeate – IBM will also be able to re-establish ties with its enterprise focus in a new way. Secondly, IBM is also engaging with Twitter. The two declared a partnership that will bring Twitter data to IBM services and software; IBM shares rose 0.03% after this was announced.

Finally, even the negatives discussed earlier may be reinterpreted positively. While calling off Roadmap 2015 may have slaughtered share prices temporarily, some analysts say that IBM has effectively “wiped the slate clean” – that the Roadmap, given IBM’s ten-quarter history, was not realistic, and that its dismissal means the company can focus on transitioning to new, better opportunities rather than managing earnings that would, considering its current revenue trends, be unavoidably disappointing.

Relatedly, while the GlobalFoundries deal has cost IBM quite some cash, strips the company of certain trademark intellectual property, and signals that IBM’s core segments are dying down, holding on to chip production would have hurt Big Blue. Stifel Nicolaus’ David Grossman also says the deal “had been telegraphed for months”: at least some facets of IBM’s business developments this quarter, therefore, were not unexpected.

This also goes for IBM’s continued focus on disposing of hardware, and accentuating services: Rometty and other executives – as well as many investors – believe it’s the right way to go forward. “We continue to evolve services, the same way we continue to evolve what our clients want in software,” CFO Martin Schroeter said. While similarly confident predictions have previously failed, it is noteworthy that the largest of them were not made by Rometty. What’s more, she has a plan for the future that evolved with Big Blue’s Q3 results, now emphasizing that IBM must “improve speed and agility” – she understands the urgency that stems from the company’s late transition, noting that “We have more to do and we need to do it faster”, and that while IBM’s strategy “is correct”, “speed of execution … needs to improve”. The hope that Rometty’s plan may work is bolstered by the fact that many of her recent schema (e.g., branching into new markets) have earned IBM at least some success, and were thus at least relatively well thought-out. While some analysts point out her intended transitions will not be easy – as has been mentioned, moving away from hardware and old services could be painful, given that much (75%) of IBM’s sales are still derived from these sectors – Rometty is doing her best to compensate via lay-offs, tax-rate reductions, and, of course, buybacks.

While the last of these three methods took considerable flack in “A Few Negatives”, some argue that stock buybacks aren’t as bad as they seem. Warren Buffett, in direct opposition to David A. Stockman, has said that buybacks can be useful to creating value by shrinking the pool of shares for sale. Other investors agree, stating that IBM’s dedication to returning capital to its shareholders has “helped [the company] outperform the market over the past 10 years, even as it struggled to boost sales”. This viewpoint, if accurate, reaffirms that there is typically a method to Rometty’s “madness”: she has been integral to buying back shares, spending more than $12 billion on IBM’s shares in the first six months of this year, and sending shareholders large dividends. In fact, if Buffett is right, then Rometty’s moves indicate that IBM as a whole never actually lost its methodical mindset to begin with: stock buybacks have been an IBM focus since 2000, and divestitures of unprofitable segments were a focus of Palmisano’s tenure (he sold IBM’s storage and commercial printing units from 2002 through to 2012, and handed the company’s PC business – including its famous ThinkPad line – to Lenovo in 2005). As much as failed predictions may appear to dictate otherwise, Rometty is, at least in part, proceeding in a decently predetermined direction.

Finally, intellectual property loss in the chip production arena shouldn’t be too large a threat to IBM – its research segment remains as strong as ever, and has recently added several high-technology successes (e.g., Watson) to its name. Further, IBM won’t completely abandon hardware research: Director of Research John E. Kelly III has said that IBM will continue to invest in chip research, and will continue to sell servers and supercomputers – it just won’t spend money on manufacturing. Instead, the chips GlobalFoundries will produce for IBM will be used for the company’s mainframe, scale-out systems, and next-generation storage systems.

Others’ Takes

“There’s a good chance that five years from now or 10 years from now, IBM will be, once again, at the top of its game.” – Vahan Janjigian, Greenwich Wealth Management CEO

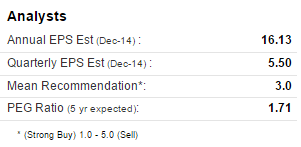

As I think we can conclude eleven pages in, IBM is no easy stock to analyze. It does, however, have its positives. As such, analyst and investor perspectives appear to waver towards either neutrality or positivity, despite October’s not-so-stunning results, as is demonstrated by Yahoo! Finance analysts’ mean recommendation.

Figure . Yahoo! Finance analysts’ mean recommendation is a 3.0: a hold, where a 1.0 is a strong buy and a 5.0 is a strong sell.

Individual analysts differ slightly, but remain generally positive in their assessments of the company. Analyst Joseph Foresi of Janney Capital Markets and others at BMO Capital Markets, for example, have praised IBM’s decision to dispose of Roadmap 2015, maintaining a neutral rating of the company.David Grossman of Stifel Nicolaus takes things a bit further: because he believes a company of IBM’s size and score is incredibly difficult to change, he does not hold Ginni Rometty at too much fault, and has maintained a buy rating where IBM is concerned, despite revenue declines.

Some prominent investors share these sentiments. Vahan Janjigian, CEO of Greenwich Wealth Management, has IBM as one of his top 10 holdings. He cautions investors to wait a little before purchasing, however, as he thinks the stock may drop lower before it rises. And then – of course – there’s Warren Buffett, whose firm – Berkshire Hathway – holds seven percent stake in IBM. One of IBM’s biggest supporters, he was not available for comment just after IBM dropped. However, Buffett was the first to say, quite some time ago, that this kind of a situation would not faze him. In fact, he explicitly mentioned that a drop akin to this one could, by limiting share availability, increase value.

Algorithmic Perspective

While algorithmic analysis is not to be considered conclusive, it is useful when combined with traditional techniques. Where such stocks as IBM are concerned, algorithmic analysis – which relies upon historical trends and other information – can be especially useful in carefully piecing apart one’s investment decisions, which may otherwise be subjective to surrounding bias.

I Know First is an investment firm that uses an uses an advanced self-learning algorithm based on artificial intelligence, machine learning, and artificial neural networks to supplement its fundamental analyses. In doing so, it predicts the flow of money in almost 2000 markets across a range of time frames (e.g., 3-days, 1-month, 1-year). It should be noted that the algorithm’s predictability (i.e., its accuracy) becomes stronger in 1-month, 3-month, and 1-year forecasts; as such, it can – when coupled with traditional analysis and careful reasoning – most effectively be used to analyze both short-term and long-term trends, but is not as convenient where intraday trading is concerned. The algorithm has seen a high degree of accuracy; as such, while it may seem tempting to disregard its predictions, cross-checking with its suggestions can be helpful in deciding where to place your money.

In particular, I Know First has previously helped investors decide how to engage with IBM. Recently, in fact, the algorithm successfully predicted the success that IBM would experience over the course of 2014, as well as the drop it would see in October 2014: this forecast was, in highlighting both negative and positive attributes of future stock performance, accurate across the 1-month, 3-month, and 1-year time frames.

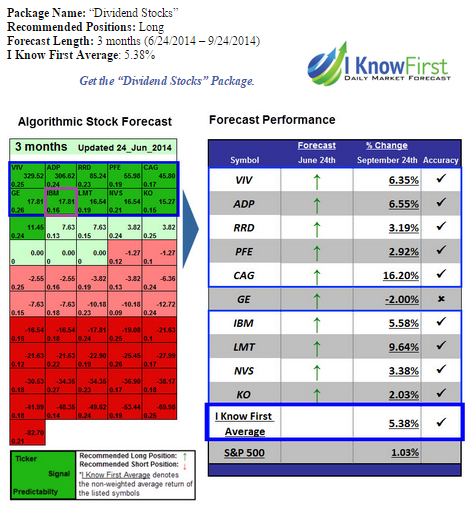

Firstly, a 3-month forecast, last updated June 24th, 2014, forecasted highly bullish activity for IBM in the 3-month time frame (Figure ). IBM was expected to be one of the ten best stocks of the below forecast from June 24th through September 24th, 2014; it held true to this prediction for a return of +5.58%.

Figure . 3-month forecast lasted updated on June 24th, 2014. IBM is shown to be strongly bullish, and is boxed in purple for emphasis. Prediction is on the left, stock performance is on the right – note that IBM performance coincided with forecasted behavior.

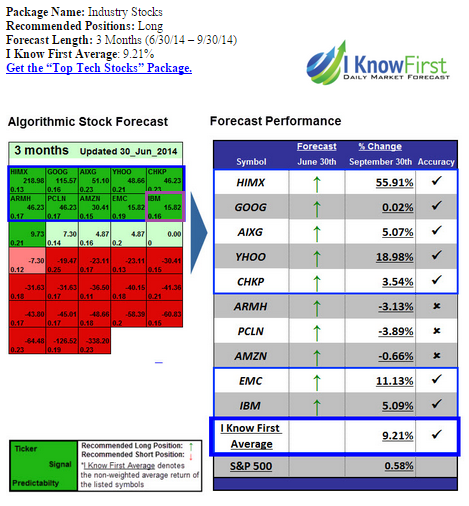

Secondly, another 3-month forecast, this time updated on June 30th, 2014, forecasted decreasingly (but nevertheless strongly) bullish activity for IBM in the 3-month time frame, with a signal of 15.82 and a predictability of 0.16 (Figure ). This prediction also showed itself to be accurate: IBM had a return of 5.09%.

Figure . 3-month forecast lasted updated on June 30th, 2014. IBM was one of the ten best stocks. As predicted, remained bullish through to September 30th.

Two things are important to note here: firstly, the first and the second forecast, taken six days apart, approach the same value; while this by no means guarantees accuracy, the forecast is at least consistent, so it may have some logical basis for its predictions. Secondly, the second forecast, while still positive, is minutely less so than the first; this may indicate a move towards the kind of bearish conditions IBM experienced in late October.

The new 1-month and 3-month forecasts generated by the I Know First algorithm, updated on November 2nd, are shown below (Figure ). Bright green signifies a highly bullish signal; light green also indicates that the forecast is bullish, but not as strongly so. Bright red, in turn, signifies a bearish forecast; correspondingly, light red indicates a bearish forecast as well, but not as negative a forecast. Each compartment contains two numbers: the strength of the signal itself (represented by the number in the middle of each box, to the right), and its predictability (found in the bottom left corner, this is the approximate level of confidence the algorithm has in the forecast).

Figure . Updated forecast for International Business Machines Corporation (NYSE:IBM). IBM’s ticker symbol – “IBM” – is boxed in purple on the top left; its position indicates that it is strongly bullish.

As is evident above, IBM’s position on the algorithmic chart indicates a strongly bullish prediction for the stock in the 1-month and 3-month time frames.

For the optimal long strategy we recommend executing your trade only when two rules hold true. The first is when the last close of the specific market is above the 5 days average. The Second when the average of the last 5 days forecast signals is “up”. If both rules are true, then it is an optimal buy.

Conclusion

While IBM recently dropped rapidly, it appears to still be a company to follow. Its core-sector revenue has stagnated, to be sure, taking with it Roadmap 2015, and drastically reducing both share prices and investor confidence. The company has also recently experienced other difficulties: it has been late in its transition to cloud and mobile, and some analysts have doubted that it can successfully complete so drastic a move, given that its underlying revenues are weak, and that it already heavily depends upon stock buyback, resulting in debt. However, IBM is nevertheless a company to watch: it has rebounded abundantly in the past, so may well do so again, especially under the leadership of CEO Rometty, who has already guided the company towards strong novel-sector growth, cutting-edge research divisions like IBM Watson, and profitable partnerships with such companies as Apple and Twitter. Cumulatively, then, given its positive attributes, predominantly neutral and positive analyst opinion, and the recommendations of I Know First’s algorithm, IBM won’t make you Blue; with 1-month and 3-month forecasts that are strongly bullish, however, it may eventually win Big.

Business relationship disclosure: I Know First Research is the analytic branch of I Know First, a financial start-up company that specializes in quantitatively predicting the stock market. This article was written and edited by Daniel Barankin, our International Business Development Project Manager. We did not receive compensation for this article (other than from Seeking Alpha), and we have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.